Estudio en escarlata

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Noviembre de 1887

A study in scarlet

Transcriber's Note: This text is prepared directly from an 1887 edition, and care has been taken to duplicate some typographical and punctuation vagaries of the original.

Contents

Índice

A study in scarlet.

Part I.

(Being a reprint from the reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D., late of the Army Medical Department.)

PRIMERA PARTE

(Reimpresión de las memorias de John H. Watson, doctor en medicina y oficial retirado del Cuerpo de Sanidad)

Chapter I.

Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Capítulo uno

Mr. Sherlock Holmes

IN the year 1878 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine of the University of London, and proceeded to Netley to go through the course prescribed for surgeons in the army. Having completed my studies there, I was duly attached to the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers as Assistant Surgeon. The regiment was stationed in India at the time, and before I could join it, the second Afghan war had broken out. On landing at Bombay, I learned that my corps had advanced through the passes, and was already deep in the enemy's country. I followed, however, with many other officers who were in the same situation as myself, and succeeded in reaching Candahar in safety, where I found my regiment, and at once entered upon my new duties.

En el año 1878 obtuve el título de doctor en medicina por la Universidad de Londres, asistiendo después en Netley a los cursos que son de rigor antes de ingresar como médico en el ejército. Concluidos allí mis estudios, fui puntualmente destinado el 5º de Fusileros de Northumberland en calidad de médico ayudante. El regimiento se hallaba por entonces estacionado en la India, y antes de que pudiera unirme a él, estalló la segunda guerra de Afganistán. Al desembarcar en Bombay me llegó la noticia de que las tropas a las que estaba agregado habían traspuesto la línea montañosa, muy dentro ya de territorio enemigo. Seguí, sin embargo, camino con muchos otros oficiales en parecida situación a la mía, hasta Candahar, donde sano y salvo, y en compañía por fin del regimiento, me incorporé sin más dilación a mi nuevo servicio.

The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it had nothing but misfortune and disaster. I was removed from my brigade and attached to the Berkshires, with whom I served at the fatal battle of Maiwand. There I was struck on the shoulder by a Jezail bullet, which shattered the bone and grazed the subclavian artery. I should have fallen into the hands of the murderous Ghazis had it not been for the devotion and courage shown by Murray, my orderly, who threw me across a pack-horse, and succeeded in bringing me safely to the British lines.

La campaña trajo a muchos honores, pero a mí sólo desgracias y calamidades. Fui separado de mi brigada e incorporado a las tropas de Berkshire, con las que estuve de servicio durante el desastre de Maiwand. En la susodicha batalla una bala de Jezail me hirió el hombro, haciéndose añicos el hueso y sufriendo algún daño la arteria subclavia. Hubiera caído en manos de los despiadados ghazis a no ser por el valor y lealtad de Murray, mi asistente, quien, tras ponerme de través sobre una caballería, logró alcanzar felizmente las líneas británicas.

Worn with pain, and weak from the prolonged hardships which I had undergone, I was removed, with a great train of wounded sufferers, to the base hospital at Peshawar. Here I rallied, and had already improved so far as to be able to walk about the wards, and even to bask a little upon the verandah, when I was struck down by enteric fever, that curse of our Indian possessions. For months my life was despaired of, and when at last I came to myself and became convalescent, I was so weak and emaciated that a medical board determined that not a day should be lost in sending me back to England. I was dispatched, accordingly, in the troopship "Orontes," and landed a month later on Portsmouth jetty, with my health irretrievably ruined, but with permission from a paternal government to spend the next nine months in attempting to improve it.

Agotado por el dolor, y en un estado de gran debilidad a causa de las muchas fatigas sufridas, fui trasladado, junto a un nutrido convoy de maltrechos compañeros de infortunio, al hospital de la base de Peshawar. Allí me rehice, y estaba ya lo bastante sano para dar alguna que otra vuelta por las salas, y orearme de tiempo en tiempo en la terraza, cuando caí víctima del tifus, el azote de nuestras posesiones indias. Durante meses no se dio un ardite por mi vida, y una vez vuelto al conocimiento de las cosas, e iniciada la convalecencia, me sentí tan extenuado, y con tan pocas fuerzas, que el consejo médico determinó sin más mi inmediato retorno a Inglaterra. Despachado en el transporte militar Orontes, al mes de travesía toqué tierra en Portsmouth, con la salud malparada para siempre y nueve meses de plazo, sufragados por un gobierno paternal, para probar a remediarla.

I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free as air—or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day will permit a man to be. Under such circumstances, I naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time at a private hotel in the Strand, leading a comfortless, meaningless existence, and spending such money as I had, considerably more freely than I ought. So alarming did the state of my finances become, that I soon realized that I must either leave the metropolis and rusticate somewhere in the country, or that I must make a complete alteration in my style of living. Choosing the latter alternative, I began by making up my mind to leave the hotel, and to take up my quarters in some less pretentious and less expensive domicile.

No tenía en Inglaterra parientes ni amigos, y era, por tanto, libre como una alondra —es decir, todo lo libre que cabe ser con un ingreso diario de once chelines y medio—. Hallándome en semejante coyuntura gravité naturalmente hacia Londres, sumidero enorme donde van a dar de manera fatal cuantos desocupados y haraganes contiene el imperio. Permanecí durante algún tiempo en un hotel del Strand, viviendo antes mal que bien, sin ningún proyecto a la vista, y gastando lo poco que tenía, con mayor liberalidad, desde luego, de la que mi posición recomendaba. Tan alarmante se hizo el estado de mis finanzas que pronto caí en la cuenta de que no me quedaban otras alternativas que decir adiós a la metrópoli y emboscarme en el campo, o imprimir un radical cambio a mi modo de vida. Elegido el segundo camino, principié por hacerme a la idea de dejar el hotel, y sentar mis reales en un lugar menos caro y pretencioso.

On the very day that I had come to this conclusion, I was standing at the Criterion Bar, when some one tapped me on the shoulder, and turning round I recognized young Stamford, who had been a dresser under me at Barts. The sight of a friendly face in the great wilderness of London is a pleasant thing indeed to a lonely man. In old days Stamford had never been a particular crony of mine, but now I hailed him with enthusiasm, and he, in his turn, appeared to be delighted to see me. In the exuberance of my joy, I asked him to lunch with me at the Holborn, and we started off together in a hansom.

No había pasado un día desde semejante decisión, cuando, hallándome en el Criterion Bar, alguien me puso la mano en el hombro, mano que al dar media vuelta reconocí como perteneciente al joven Stamford, el antiguo practicante a mis órdenes en el Barts. La vista de una cara amiga en la jungla londinense resulta en verdad de gran consuelo al hombre solitario. En los viejos tiempos no habíamos sido Stamford y yo lo que se dice uña y carne, pero ahora lo acogí con entusiasmo, y él, por su parte, pareció contento de verme. En ese arrebato de alegría lo invité a que almorzara conmigo en el Holborn, y juntos subimos a un coche de caballos...

"Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?" he asked in undisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets. "You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut."

—Pero ¿qué ha sido de usted, Watson? —me preguntó sin embozar su sorpresa mientras el traqueteante vehículo se abría camino por las pobladas calles de Londres—. Está delgado como un arenque y más negro que una nuez.

I gave him a short sketch of my adventures, and had hardly concluded it by the time that we reached our destination.

Le hice un breve resumen de mis aventuras, y apenas si había concluido cuando llegamos a destino.

"Poor devil!" he said, commiseratingly, after he had listened to my misfortunes. "What are you up to now?"

—¡Pobre de usted! —dijo en tono conmiserativo al escuchar mis penalidades—. ¿Y qué proyectos tiene?

"Looking for lodgings," I answered. "Trying to solve the problem as to whether it is possible to get comfortable rooms at a reasonable price."

—Busco alojamiento —repuse—. Quiero ver si me las arreglo para vivir a un precio razonable.

"That's a strange thing," remarked my companion; "you are the second man to-day that has used that expression to me."

—Cosa extraña —comentó mi compañero—, es usted la segunda persona que ha empleado esas palabras en el día de hoy.

"And who was the first?" I asked.

—¿Y quién fue la primera? —pregunté.

"A fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital. He was bemoaning himself this morning because he could not get someone to go halves with him in some nice rooms which he had found, and which were too much for his purse."

—Un tipo que está trabajando en el laboratorio de química, en el hospital. Andaba quejándose esta mañana de no tener a nadie con quien compartir ciertas habitaciones que ha encontrado, bonitas a lo que parece, si bien de precio demasiado abultado para su bolsillo.

"By Jove!" I cried, "if he really wants someone to share the rooms and the expense, I am the very man for him. I should prefer having a partner to being alone."

—¡Demonio! —exclamé—, si realmente está dispuesto a dividir el gasto y las habitaciones, soy el hombre que necesita. Prefiero tener un compañero antes que vivir solo.

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wine-glass. "You don't know Sherlock Holmes yet," he said; "perhaps you would not care for him as a constant companion."

El joven Stamford, el vaso en la mano, me miró de forma un tanto extraña.

—No conoce todavía a Sherlock Holmes —dijo—, podría llegar a la conclusión de que no es exactamente el tipo de persona que a uno le gustaría tener siempre por vecino.

"Why, what is there against him?"

—¿Sí? ¿Qué habla en contra suya?

"Oh, I didn't say there was anything against him. He is a little queer in his ideas—an enthusiast in some branches of science. As far as I know he is a decent fellow enough."

—Oh, en ningún momento he sostenido que haya nada contra él. Se trata de un hombre de ideas un tanto peculiares..., un entusiasta de algunas ramas de la ciencia. Hasta donde se me alcanza, no es mala persona.

"A medical student, I suppose?" said I.

—Naturalmente sigue la carrera médica —inquirí.

"No—I have no idea what he intends to go in for. I believe he is well up in anatomy, and he is a first-class chemist; but, as far as I know, he has never taken out any systematic medical classes. His studies are very desultory and eccentric, but he has amassed a lot of out-of-the way knowledge which would astonish his professors."

—No... Nada sé de sus proyectos. Creo que anda versado en anatomía, y es un químico de primera clase; pero según mis informes, no ha asistido sistemáticamente a ningún curso de medicina. Persigue en el estudio rutas extremadamente dispares y excéntricas, si bien ha hecho acopio de una cantidad tal y tan desusada de conocimientos, que quedarían atónitos no pocos de sus profesores.

"Did you never ask him what he was going in for?" I asked.

—¿Le ha preguntado alguna vez qué se trae entre manos?

"No; he is not a man that it is easy to draw out, though he can be communicative enough when the fancy seizes him."

—No; no es hombre que se deje llevar fácilmente a confidencias, aunque puede resultar comunicativo cuando está en vena.

"I should like to meet him," I said. "If I am to lodge with anyone, I should prefer a man of studious and quiet habits. I am not strong enough yet to stand much noise or excitement. I had enough of both in Afghanistan to last me for the remainder of my natural existence. How could I meet this friend of yours?"

—Me gustaría conocerle —dije—. Si he de partir la vivienda con alguien, prefiero que sea persona tranquila y consagrada al estudio. No me siento aún lo bastante fuerte para sufrir mucho alboroto o una excesiva agitación. Afganistán me ha dispensado ambas cosas en grado suficiente para lo que me resta de vida. ¿Cómo podría entrar en contacto con este amigo de usted?

"He is sure to be at the laboratory," returned my companion. "He either avoids the place for weeks, or else he works there from morning to night. If you like, we shall drive round together after luncheon."

—Ha de hallarse con seguridad en el laboratorio —repuso mi compañero—. O se ausenta de él durante semanas, o entra por la mañana para no dejarlo hasta la noche. Si usted quiere, podemos llegarnos allí después del almuerzo.

"Certainly," I answered, and the conversation drifted away into other channels.

—Desde luego —contesté, y la conversación tiró por otros derroteros.

As we made our way to the hospital after leaving the Holborn, Stamford gave me a few more particulars about the gentleman whom I proposed to take as a fellow-lodger.

Una vez fuera de Holborn y rumbo ya al laboratorio, Stamford añadió algunos detalles sobre el caballero que llevaba trazas de convertirse en mi futuro coinquilino.

"You mustn't blame me if you don't get on with him," he said; "I know nothing more of him than I have learned from meeting him occasionally in the laboratory. You proposed this arrangement, so you must not hold me responsible."

—Sepa exculparme si no llega a un acuerdo con él —dijo—, nuestro trato se reduce a unos cuantos y ocasionales encuentros en el laboratorio. Ha sido usted quien ha propuesto este arreglo, de modo que quedo exento de toda responsabilidad.

"If we don't get on it will be easy to part company," I answered. "It seems to me, Stamford," I added, looking hard at my companion, "that you have some reason for washing your hands of the matter. Is this fellow's temper so formidable, or what is it? Don't be mealy-mouthed about it."

—Si no congeniamos bastará que cada cual siga su camino —repuse—. Me da la sensación, Stamford —añadí mirando fijamente a mi compañero—, de que tiene usted razones para querer lavarse las manos en este negocio. ¿Tan formidable es la destemplanza de nuestro hombre? Hable sin reparos.

"It is not easy to express the inexpressible," he answered with a laugh. "Holmes is a little too scientific for my tastes—it approaches to cold-bloodedness. I could imagine his giving a friend a little pinch of the latest vegetable alkaloid, not out of malevolence, you understand, but simply out of a spirit of inquiry in order to have an accurate idea of the effects. To do him justice, I think that he would take it himself with the same readiness. He appears to have a passion for definite and exact knowledge."

—No es cosa sencilla expresar lo inexpresable —repuso riendo—. Holmes posee un carácter demasiado científico para mi gusto..., un carácter que raya en la frigidez. Me lo figuro ofreciendo a un amigo un pellizco del último alcaloide vegetal, no con malicia, entiéndame, sino por la pura curiosidad de investigar a la menuda sus efectos. Y si he de hacerle justicia, añadiré que en mi opinión lo engulliría él mismo con igual tranquilidad. Se diría que habita en su persona la pasión por el conocimiento detallado y preciso.

"Very right too."

—Encomiable actitud.

"Yes, but it may be pushed to excess. When it comes to beating the subjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick, it is certainly taking rather a bizarre shape."

—Y a veces extremosa... Cuando le induce a aporrear con un bastón los cadáveres, en la sala de disección, se pregunta uno si no está revistiendo acaso una forma en exceso peculiar.

"Beating the subjects!"

—¡Aporrear los cadáveres!

"Yes, to verify how far bruises may be produced after death. I saw him at it with my own eyes."

—Sí, a fin de ver hasta qué punto pueden producirse magulladuras en un cuerpo muerto. Lo he contemplado con mis propios ojos.

"And yet you say he is not a medical student?"

—¿Y dice usted que no estudia medicina?

"No. Heaven knows what the objects of his studies are. But here we are, and you must form your own impressions about him." As he spoke, we turned down a narrow lane and passed through a small side-door, which opened into a wing of the great hospital. It was familiar ground to me, and I needed no guiding as we ascended the bleak stone staircase and made our way down the long corridor with its vista of whitewashed wall and dun-coloured doors. Near the further end a low arched passage branched away from it and led to the chemical laboratory.

—No. Sabe Dios cuál será el objeto de tales investigaciones... Pero ya hemos llegado, y podrá usted formar una opinión sobre el personaje.

Cuando esto decía enfilamos una callejuela, y a través de una pequeña puerta lateral fuimos a dar a una de las alas del gran hospital. Siéndome el terreno familiar, no precisé guía para seguir mi itinerario por la lúgubre escalera de piedra y a través luego del largo pasillo de paredes encaladas y puertas color castaño. Casi al otro extremo, un corredor abovedado y de poca altura torcía hacia uno de los lados, conduciendo al laboratorio de química.

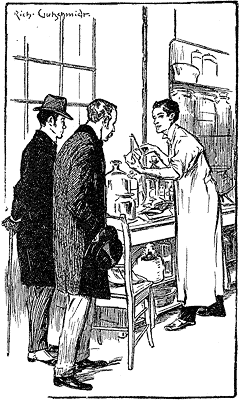

This was a lofty chamber, lined and littered with countless bottles. Broad, low tables were scattered about, which bristled with retorts, test-tubes, and little Bunsen lamps, with their blue flickering flames. There was only one student in the room, who was bending over a distant table absorbed in his work. At the sound of our steps he glanced round and sprang to his feet with a cry of pleasure. "I've found it! I've found it," he shouted to my companion, running towards us with a test-tube in his hand. "I have found a re-agent which is precipitated by hœmoglobin, and by nothing else." Had he discovered a gold mine, greater delight could not have shone upon his features.

"hœmoglobin": should be haemoglobin.

Era éste una habitación de elevado techo, llena toda de frascos que se alineaban a lo largo de las paredes o yacían desperdigados por el suelo. Aquí y allá aparecían unas mesas bajas y anchas erizadas de retortas, tubos de ensayo y pequeñas lámparas Bunsen con su azul y ondulante lengua de fuego. En la habitación hacía guardia un solitario estudiante que, absorto en su trabajo, se inclinaba sobre una mesa apartada. Al escuchar nuestros pasos volvió la cabeza, y saltando en pie dejó oír una exclamación de júbilo.

—¡Ya lo tengo! ¡Ya lo tengo! —gritó a mi acompañante mientras corría hacia nosotros con un tubo de ensayo en la mano—. He hallado un reactivo que precipita con la hemoglobina y solamente con ella.

El descubrimiento de una mina de oro no habría encendido placer más intenso en aquel rostro.

"Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes," said Stamford, introducing us.

—Doctor Watson, el señor Sherlock Holmes —anunció Stamford a modo de presentación.

"How are you?" he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. "You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive."

—Encantado —dijo cordialmente mientras me estrechaba la mano con una fuerza que su aspecto casi desmentía—. Por lo que veo, ha estado usted en tierras afganas.

"How on earth did you know that?" I asked in astonishment.

—¿Cómo diablos ha podido adivinarlo? —pregunté, lleno de asombro.

"Never mind," said he, chuckling to himself. "The question now is about hoemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?"

—No tiene importancia —repuso él riendo por lo bajo—. Volvamos a la hemoglobina. ¿Sin duda percibe usted el alcance de mi descubrimiento?

"It is interesting, chemically, no doubt," I answered, "but practically——"

—Interesante desde un punto de vista químico —contesté—, pero, en cuanto a su aplicación práctica...

"Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don't you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!" He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. "Let us have some fresh blood," he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. "Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction." As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar.

—Por Dios, se trata del más útil hallazgo que en el campo de la Medina Legal haya tenido lugar durante los últimos años. Fíjese: nos proporciona una prueba infalible para descubrir las manchas de sangre. ¡Venga usted a verlo!

Era tal su agitación que me agarró de la manga de la chaqueta, arrastrándome hasta el tablero donde había estado realizando sus experimentos.

—Hagámonos con un poco de sangre fresca —dijo, clavándose en el dedo una larga aguja y vertiendo en una probeta de laboratorio la gota manada de la herida.

—Ahora añado esta pequeña cantidad de sangre a un litro de agua. Puede usted observar que la mezcla resultante ofrece la apariencia del agua pura. La proporción de sangre no excederá de uno a un millón. No me cabe duda, sin embargo, de que nos las compondremos para obtener la reacción característica.

Mientras tal decía, arrojó en el recipiente unos pocos cristales blancos, agregando luego algunas gotas de cierto líquido transparente. En el acto la mezcla adquirió un apagado color caoba, en tanto que se posaba sobre el fondo de la vasija de vidrio un polvo parduzco.

"Ha! ha!" he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. "What do you think of that?"

—¡Ajá! —exclamó, dando palmadas y alborozado como un niño con zapatos nuevos—. ¿Qué me dice ahora?

"It seems to be a very delicate test," I remarked.

—Fino experimento —repuse.

"Beautiful! beautiful! The old Guiacum test was very clumsy and uncertain. So is the microscopic examination for blood corpuscles. The latter is valueless if the stains are a few hours old. Now, this appears to act as well whether the blood is old or new. Had this test been invented, there are hundreds of men now walking the earth who would long ago have paid the penalty of their crimes."

—¡Magnífico! ¡Magnífico! La tradicional prueba del guayaco resultaba muy tosca e insegura. Lo mismo cabe decir del examen de los corpúsculos de sangre... Este último es inútil cuando las manchas cuentan arriba de unas pocas horas. Sin embargo, acabamos de dar con un procedimiento que actúa tanto si la sangre es vieja como nueva. A ser mi hallazgo más temprano, muchas gentes que ahora pasean por la calle hubieran pagado tiempo atrás las penas a que sus crímenes les hacen acreedoras.

"Indeed!" I murmured.

—Caramba... —murmuré.

"Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man is suspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. His linen or clothes are examined, and brownish stains discovered upon them. Are they blood stains, or mud stains, or rust stains, or fruit stains, or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert, and why? Because there was no reliable test. Now we have the Sherlock Holmes' test, and there will no longer be any difficulty."

—Los casos criminales giran siempre alrededor del mismo punto. A veces un hombre resulta sospechoso de un crimen meses más tarde de cometido éste; se someten a examen sus trajes y ropa blanca: aparecen unas manchas parduzcas. ¿Son manchas de sangre, de barro, de óxido, acaso de fruta? Semejante extremo ha sumido en la confusión a más de un experto, y ¿sabe usted por qué? Por la inexistencia de una prueba segura. Sherlock Holmes ha aportado ahora esa prueba, y queda el camino despejado en lo venidero.

His eyes fairly glittered as he spoke, and he put his hand over his heart and bowed as if to some applauding crowd conjured up by his imagination.

Había al hablar destellos en sus ojos; descansó la palma de la mano a la altura del corazón, haciendo después una reverencia, como si delante suyo se hallase congregada una imaginaria multitud.

"You are to be congratulated," I remarked, considerably surprised at his enthusiasm.

—Merece usted que se le felicite —apunté, no poco sorprendido de su entusiasmo.

"There was the case of Von Bischoff at Frankfort last year. He would certainly have been hung had this test been in existence. Then there was Mason of Bradford, and the notorious Muller, and Lefevre of Montpellier, and Samson of new Orleans. I could name a score of cases in which it would have been decisive."

—¿Recuerda el pasado año el caso de Von Bischoff, en Frankfurt? De haber existido esta prueba, mi experimento le habría llevado en derechura a la horca. ¡Y qué decir de Mason, el de Bradford, o del célebre Muller, o de Lefévre de Montpellier, o de Samson el de Nueva Orleans! Una veintena de casos me acuden a la mente en los que la prueba hubiera sido decisiva.

"You seem to be a walking calendar of crime," said Stamford with a laugh. "You might start a paper on those lines. Call it the 'Police News of the Past.'"

—Parece usted un almanaque viviente de hechos criminales —apuntó Stamford con una carcajada—. ¿Por qué no publica algo? Podría titularlo «Noticiario policíaco de tiempos pasados».

"Very interesting reading it might be made, too," remarked Sherlock Holmes, sticking a small piece of plaster over the prick on his finger. "I have to be careful," he continued, turning to me with a smile, "for I dabble with poisons a good deal." He held out his hand as he spoke, and I noticed that it was all mottled over with similar pieces of plaster, and discoloured with strong acids.

—No sería ningún disparate —repuso Sherlock Holmes poniendo un pedacito de parche sobre el pinchazo—. He de andar con tiento —prosiguió mientras se volvía sonriente hacia mí—, porque manejo venenos con mucha frecuencia.

Al tiempo que hablaba alargó la mano, y eché de ver que la tenía moteada de parches similares y descolorida por el efecto de ácidos fuertes.

"We came here on business," said Stamford, sitting down on a high three-legged stool, and pushing another one in my direction with his foot. "My friend here wants to take diggings, and as you were complaining that you could get no one to go halves with you, I thought that I had better bring you together."

—Hemos venido a tratar un negocio —dijo Stamford tomando asiento en un elevado taburete de tres patas, y empujando otro hacia mí con el pie—. Este señor anda buscando dónde cobijarse, y como se lamentaba usted de no encontrar nadie que quisiera ir a medias en la misma operación, he creído buena la idea de reunirlos a los dos.

Sherlock Holmes seemed delighted at the idea of sharing his rooms with me. "I have my eye on a suite in Baker Street," he said, "which would suit us down to the ground. You don't mind the smell of strong tobacco, I hope?"

A Sherlock Holmes pareció seducirle el proyecto de dividir su vivienda conmigo.

—Tengo echado el ojo a unas habitaciones en Baker Street —dijo—, que nos vendrían de perlas. Espero que no le repugne el olor a tabaco fuerte.

"I always smoke 'ship's' myself," I answered.

—No gasto otro —repuse.

"That's good enough. I generally have chemicals about, and occasionally do experiments. Would that annoy you?"

—Hasta ahí vamos bastante bien. Suelo trastear con sustancias químicas y de vez en cuanto realizo algún experimento. ¿Le importa?

"By no means."

—En absoluto.

"Let me see—what are my other shortcomings. I get in the dumps at times, and don't open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I am sulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I'll soon be right. What have you to confess now? It's just as well for two fellows to know the worst of one another before they begin to live together."

—Veamos..., cuáles son mis otros inconvenientes. De tarde en tarde me pongo melancólico y no despego los labios durante días. No lo atribuya usted nunca a mal humor o resentimiento. Déjeme sencillamente a mi aire y verá qué pronto me enderezo. En fin, ¿qué tiene usted a su vez que confesarme? Es aconsejable que dos individuos estén impuestos sobre sus peores aspectos antes de que se decidan a vivir juntos.

I laughed at this cross-examination. "I keep a bull pup," I said, "and I object to rows because my nerves are shaken, and I get up at all sorts of ungodly hours, and I am extremely lazy. I have another set of vices when I'm well, but those are the principal ones at present."

Me hizo reír semejante interrogatorio.

—Soy dueño de un cachorrito —dije—, y desapruebo los estrépitos porque mis nervios están destrozados... y me levanto a las horas más inesperadas y me declaro, en fin, perezoso en extremo. Guardo otra serie de vicios para los momentos de euforia, aunque los enumerados ocupan a la sazón un lugar preeminente.

"Do you include violin-playing in your category of rows?" he asked, anxiously.

—¿Entra para usted el violín en la categoría de lo estrepitoso? —me preguntó muy alarmado.

"It depends on the player," I answered. "A well-played violin is a treat for the gods—a badly-played one——"

—Según quién lo toque —repuse—. Un violín bien tratado es un regalo de los dioses, un violín en manos poco diestras...

"Oh, that's all right," he cried, with a merry laugh. "I think we may consider the thing as settled—that is, if the rooms are agreeable to you."

—Magnífico —concluyó con una risa alegre—. Creo que puede considerarse el trato zanjado..., siempre y cuando dé usted el visto bueno a las habitaciones.

"When shall we see them?"

—¿Cuándo podemos visitarlas?

"Call for me here at noon to-morrow, and we'll go together and settle everything," he answered.

—Venga usted a recogerme mañana a mediodía; saldremos después juntos y quedará todo arreglado.

"All right—noon exactly," said I, shaking his hand.

—De acuerdo, a las doce en punto —repuse estrechándole la mano.

We left him working among his chemicals, and we walked together towards my hotel.

Lo dejamos enzarzado con sus productos químicos y juntos fuimos caminando hacia el hotel.

"By the way," I asked suddenly, stopping and turning upon Stamford, "how the deuce did he know that I had come from Afghanistan?"

—Por cierto —pregunté de pronto, deteniendo la marcha y dirigiéndome a Stamford—, ¿cómo demonios ha caído en la cuenta de que venía yo de Afganistán?

My companion smiled an enigmatical smile. "That's just his little peculiarity," he said. "A good many people have wanted to know how he finds things out."

Sobre el rostro de mi compañero se insinuó una enigmática sonrisa.

—He ahí una peculiaridad de nuestro hombre —dijo—. Es mucha la gente a la que intriga esa facultad suya de adivinar las cosas.

"Oh! a mystery is it?" I cried, rubbing my hands. "This is very piquant. I am much obliged to you for bringing us together. 'The proper study of mankind is man,' you know."

—¡Caramba! ¿Se trata de un misterio? —exclamé frotándome las manos—. Esto empieza a ponerse interesante. Realmente, le agradezco infinito su presentación... Como reza el dicho, «no hay objeto de estudio más digno del hombre que el hombre mismo».

"You must study him, then," Stamford said, as he bade me good-bye. "You'll find him a knotty problem, though. I'll wager he learns more about you than you about him. Good-bye."

—Aplíquese entonces a la tarea de estudiar a su amigo —dijo Stamford a modo de despedida—. Aunque no le arriendo la ganancia. Verá como acaba sabiendo él mucho más de usted, que usted de él... Adiós.

"Good-bye," I answered, and strolled on to my hotel, considerably interested in my new acquaintance.

—Adiós —repuse, y proseguí sin prisas mi camino hacia el hotel, no poco intrigado por el individuo que acababa de conocer.

Chapter II.

The science of deduction.

Capítulo dos

La ciencia de la deducción

WE met next day as he had arranged, and inspected the rooms at No. 221b, Baker Street, of which he had spoken at our meeting. They consisted of a couple of comfortable bed-rooms and a single large airy sitting-room, cheerfully furnished, and illuminated by two broad windows. So desirable in every way were the apartments, and so moderate did the terms seem when divided between us, that the bargain was concluded upon the spot, and we at once entered into possession. That very evening I moved my things round from the hotel, and on the following morning Sherlock Holmes followed me with several boxes and portmanteaus. For a day or two we were busily employed in unpacking and laying out our property to the best advantage. That done, we gradually began to settle down and to accommodate ourselves to our new surroundings.

"221B": the B is in small caps

Nos vimos al día siguiente, según lo acordado, para inspeccionar las habitaciones del 221B de Baker Street a que se había hecho alusión durante nuestro encuentro. Consistían en dos confortables dormitorios y una única sala de estar, alegre y ventilada, con dos amplios ventanales por los que entraba la luz. Tan conveniente en todos los aspectos nos pareció el apartamento y tan moderado su precio, una vez dividido entre los dos, que el trato se cerró de inmediato y, sin más dilaciones, tomamos posesión de la vivienda. Esa misma tarde procedí a mudar mis pertenencias del hotel a la casa, y a la otra mañana Sherlock Holmes hizo lo correspondiente con las suyas, presentándose con un equipaje compuesto de maletas y múltiples cajas. Durante uno o dos días nos entregamos a la tarea de desembalar las cosas y colocarlas lo mejor posible. Salvado semejante trámite, fue ya cuestión de hacerse al paisaje circundante e ir echando raíces nuevas.

Holmes was certainly not a difficult man to live with. He was quiet in his ways, and his habits were regular. It was rare for him to be up after ten at night, and he had invariably breakfasted and gone out before I rose in the morning. Sometimes he spent his day at the chemical laboratory, sometimes in the dissecting-rooms, and occasionally in long walks, which appeared to take him into the lowest portions of the City. Nothing could exceed his energy when the working fit was upon him; but now and again a reaction would seize him, and for days on end he would lie upon the sofa in the sitting-room, hardly uttering a word or moving a muscle from morning to night. On these occasions I have noticed such a dreamy, vacant expression in his eyes, that I might have suspected him of being addicted to the use of some narcotic, had not the temperance and cleanliness of his whole life forbidden such a notion.

As the weeks went by, my interest in him and my curiosity as to his aims in life, gradually deepened and increased. His very person and appearance were such as to strike the attention of the most casual observer. In height he was rather over six feet, and so excessively lean that he seemed to be considerably taller. His eyes were sharp and piercing, save during those intervals of torpor to which I have alluded; and his thin, hawk-like nose gave his whole expression an air of alertness and decision. His chin, too, had the prominence and squareness which mark the man of determination. His hands were invariably blotted with ink and stained with chemicals, yet he was possessed of extraordinary delicacy of touch, as I frequently had occasion to observe when I watched him manipulating his fragile philosophical instruments.

No resultaba ciertamente Holmes hombre de difícil convivencia. Sus maneras eran suaves y sus hábitos regulares. Pocas veces le sorprendían las diez de la noche fuera de la cama, e indefectiblemente, al levantarme yo por la mañana, había tomado ya el desayuno y enfilado la calle. Algunos de sus días transcurrían íntegros en el laboratorio de química o en la sala de disección, destinando otros, ocasionalmente, a largos paseos que parecían llevarle hasta los barrios más bajos de la ciudad. Cuando se apoderaba de él la fiebre del trabajo era capaz de desplegar una energía sin parangón; pero a trechos y con puntualidad fatal, caía en un extraño estado de abulia, y entonces, y durante días, permanecía extendido sobre el sofá de la sala de estar, sin mover apenas un músculo o pronunciar palabra de la mañana a la noche. En tales ocasiones no dejaba de percibir en sus ojos cierta expresión perdida y como ausente que, a no ser por la templanza y limpieza de su vida toda, me habría atrevido a imputar al efecto de algún narcótico. Conforme pasaban las semanas, mi interés por él y la curiosidad que su proyecto de vida suscitaba en mí, fueron haciéndose cada vez más patentes y profundos. Su misma apariencia y aspecto externos eran a propósito para llamar la atención del más casual observador. En altura andaba antes por encima que por debajo de los seis pies, aunque la delgadez extrema exageraba considerablemente esa estatura. Los ojos eran agudos y penetrantes, salvo en los períodos de sopor a que he aludido, y su fina nariz de ave rapaz le daba no sé qué aire de viveza y determinación. La barbilla también, prominente y maciza, delataba en su dueño a un hombre de firmes resoluciones. Las manos aparecían siempre manchadas de tinta y distintos productos químicos, siendo, sin embargo, de una exquisita delicadeza, como innumerables veces eché de ver por el modo en que manejaba Holmes sus frágiles instrumentos de física.

The reader may set me down as a hopeless busybody, when I confess how much this man stimulated my curiosity, and how often I endeavoured to break through the reticence which he showed on all that concerned himself. Before pronouncing judgment, however, be it remembered, how objectless was my life, and how little there was to engage my attention. My health forbade me from venturing out unless the weather was exceptionally genial, and I had no friends who would call upon me and break the monotony of my daily existence. Under these circumstances, I eagerly hailed the little mystery which hung around my companion, and spent much of my time in endeavouring to unravel it.

Acaso el lector me esté calificando ya de entrometido impenitente en vista de lo mucho que este hombre excitaba mi curiosidad y de la solicitud impertinente con que procuraba yo vencer la reserva en que se hallaba envuelto todo lo que a él concernía. No sería ecuánime sin embargo, antes de dictar sentencia, echar en olvido hasta qué punto sin objeto era entonces mi vida, y qué pocas cosas a la sazón podían animarla. Siendo el que era mi estado de salud, sólo en días de tiempo extraordinariamente benigno me estaba permitido aventurarme al espacio exterior, faltándome, los demás, amigos con quienes endulzar la monotonía de mi rutina cotidiana. En semejantes circunstancias, acogí casi con entusiasmo el pequeño misterio que rodeaba a mi compañero, así como la oportunidad de matar el tiempo probando a desvelarlo.

He was not studying medicine. He had himself, in reply to a question, confirmed Stamford's opinion upon that point. Neither did he appear to have pursued any course of reading which might fit him for a degree in science or any other recognized portal which would give him an entrance into the learned world. Yet his zeal for certain studies was remarkable, and within eccentric limits his knowledge was so extraordinarily ample and minute that his observations have fairly astounded me. Surely no man would work so hard or attain such precise information unless he had some definite end in view. Desultory readers are seldom remarkable for the exactness of their learning. No man burdens his mind with small matters unless he has some very good reason for doing so.

No seguía la carrera médica. Él mismo, respondiendo a cierta pregunta, había confirmado el parecer de Stamford sobre semejante punto. Tampoco parecía empeñado en suerte alguna de estudio que pudiera auparle hasta un título científico, o abrirle otra cualquiera de las reconocidas puertas por donde se accede al mundo académico. Pese a todo, el celo puesto en determinadas labores era notable, y sus conocimientos, excéntricamente circunscritos a determinados campos, tan amplios y escrupulosos que daban lugar a observaciones sencillamente asombrosas. Imposible resultaba que un trabajo denodado y una información en tal grado exacta no persiguieran un fin concreto. El lector poco sistemático no se caracteriza por la precisión de los datos acumulados en el curso de sus lecturas. Nadie satura su inteligencia con asuntos menudos a menos que tenga alguna razón de peso para hacerlo así.

His ignorance was as remarkable as his knowledge. Of contemporary literature, philosophy and politics he appeared to know next to nothing. Upon my quoting Thomas Carlyle, he inquired in the naivest way who he might be and what he had done. My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That any civilized human being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the earth travelled round the sun appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realize it.

Si sabía un número de cosas fuera de lo común, ignoraba otras tantas de todo el mundo conocidas. De literatura contemporánea, filosofía y política, estaba casi completamente en ayunas. Cierta vez que saqué yo a colación el nombre de Tomás Carlyle, me preguntó, con la mayor inocencia, quién era aquél y lo que había hecho. Mi estupefacción llegó sin embargo a su cenit cuando descubrí por casualidad que ignoraba la teoría copernicana y la composición del sistema solar. El que un hombre civilizado desconociese en nuestro siglo XIX que la tierra gira en torno al sol, se me antojó un hecho tan extraordinario que apenas si podía darle crédito.

"You appear to be astonished," he said, smiling at my expression of surprise. "Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget it."

—Parece usted sorprendido —dijo sonriendo ante mi expresión de asombro—. Ahora que me ha puesto usted al corriente, haré lo posible por olvidarlo.

"To forget it!"

—¡Olvidarlo!

"You see," he explained, "I consider that a man's brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skilful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones."

—Entiéndame —explicó—, considero que el cerebro de cada cual es como una pequeña pieza vacía que vamos amueblando con elementos de nuestra elección. Un necio echa mano de cuanto encuentra a su paso, de modo que el conocimiento que pudiera serle útil, o no encuentra cabida o, en el mejor de los casos, se halla tan revuelto con las demás cosas que resulta difícil dar con él. El operario hábil selecciona con sumo cuidado el contenido de ese vano disponible que es su cabeza. Sólo de herramientas útiles se compondrá su arsenal, pero éstas serán abundantes y estarán en perfecto estado. Constituye un grave error el suponer que las paredes de la pequeña habitación son elásticas o capaces de dilatarse indefinidamente. A partir de cierto punto, cada nuevo dato añadido desplaza necesariamente a otro que ya poseíamos. Resulta por tanto de inestimable importancia vigilar que los hechos inútiles no arrebaten espacio a los útiles.

"But the Solar System!" I protested.

—¡Sí, pero el sistema solar...! —protesté.

"What the deuce is it to me?" he interrupted impatiently; "you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work."

—¿Y qué se me da a mí el sistema solar? —interrumpió ya impacientado—: dice usted que giramos en torno al sol... Que lo hiciéramos alrededor de la luna no afectaría un ápice a cuanto soy o hago.

I was on the point of asking him what that work might be, but something in his manner showed me that the question would be an unwelcome one. I pondered over our short conversation, however, and endeavoured to draw my deductions from it. He said that he would acquire no knowledge which did not bear upon his object. Therefore all the knowledge which he possessed was such as would be useful to him. I enumerated in my own mind all the various points upon which he had shown me that he was exceptionally well-informed. I even took a pencil and jotted them down. I could not help smiling at the document when I had completed it. It ran in this way—

Estuve entonces a punto de interrogarle sobre eso que él hacía, pero un no sé qué en su actitud me dio a entender que semejante pregunta no sería de su agrado. No dejé de reflexionar, sin embargo, acerca de nuestra conversación y las pistas que ella me insinuaba. Había mencionado su propósito de no entrometerse en conocimiento alguno que no atañera a su trabajo. Por tanto, todos los datos que atesoraba le reportaban por fuerza cierta utilidad. Enumeraré mentalmente los distintos asuntos sobre los que había demostrado estar excepcionalmente bien informado. Incluso tomé un lápiz y los fui poniendo por escrito. No pude contener una sonrisa cuando vi el documento en toda su extensión. Decía así:

| 1. | Knowledge of | Literature.-Nil. |

| 2. | Philosophy.-Nil. | |

| 3. | Astronomy.-Nil. | |

| 4. | Politics.-Feeble. | |

| 5. | Botany.-Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening. | |

| 6. | Geology.-Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them. | |

| 7. | Chemistry.-Profound. | |

| 8. | Anatomy.-Accurate, but unsystematic. | |

| 9. | Sensational Literature.-Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century. | |

| 10. | Plays the violin well. | |

| 11. | Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman. | |

| 12. | Has a good practical knowledge of British law. | |

«Sherlock Holmes; sus límites. 1. Conocimientos de Literatura: ninguno. 2. Conocimientos de Filosofía: ninguno. 3. Conocimientos de Astronomía: ninguno. 4. Conocimientos de Política: escasos. 5. Conocimientos de Botánica: desiguales. Al día en lo que atañe a la belladona, el opio y los venenos en general. Nulos en lo referente a la jardinería. 6. Conocimientos de Geología: prácticos aunque restringidos. De una ojeada distingue un suelo geológico de otro. Después de un paseo me ha enseñado las manchas de barro de sus pantalones y ha sabido decirme, por la consistencia y color de la tierra, a qué parte de Londres correspondía cada una. 7. Conocimientos de Química: profundos. 8. Conocimientos de Anatomía: exactos, pero poco sistemáticos. 9. Conocimientos de literatura sensacionalista: inmensos. Parece conocer todos los detalles de cada hecho macabro acaecido en nuestro siglo. 10. Toca bien el violín. 11. Experto boxeador, y esgrimista de palo y espada. 12. Familiarizado con los aspectos prácticos de la ley inglesa.»

When I had got so far in my list I threw it into the fire in despair. "If I can only find what the fellow is driving at by reconciling all these accomplishments, and discovering a calling which needs them all," I said to myself, "I may as well give up the attempt at once."

Al llegar a este punto, desesperado, arrojé la lista al fuego. «Si para adivinar lo que este tipo se propone —me dije— he de buscar qué profesión corresponde al común denominador de sus talentos, puedo ya darme por vencido.»

I see that I have alluded above to his powers upon the violin. These were very remarkable, but as eccentric as all his other accomplishments. That he could play pieces, and difficult pieces, I knew well, because at my request he has played me some of Mendelssohn's Lieder, and other favourites. When left to himself, however, he would seldom produce any music or attempt any recognized air. Leaning back in his arm-chair of an evening, he would close his eyes and scrape carelessly at the fiddle which was thrown across his knee. Sometimes the chords were sonorous and melancholy. Occasionally they were fantastic and cheerful. Clearly they reflected the thoughts which possessed him, but whether the music aided those thoughts, or whether the playing was simply the result of a whim or fancy was more than I could determine. I might have rebelled against these exasperating solos had it not been that he usually terminated them by playing in quick succession a whole series of my favourite airs as a slight compensation for the trial upon my patience.

Observo haber aludido poco más arriba a su aptitud para el violín. Era ésta notable, aunque no menos peregrina que todas las restantes. Que podía ejecutar piezas musicales, y de las difíciles, lo sabía de sobra, ya que a petición mía había reproducido las notas de algunos lieder de Mendelssohn y otras composiciones de mi elección. Cuando se dejaba llevar de su gusto, rara vez arrancaba sin embargo a su instrumento música o aires reconocibles. Recostado en su butaca durante toda una tarde, cerraba los ojos y con ademán descuidado arañaba las cuerdas del violín, colocado de través sobre una de sus rodillas. Unas veces eran las notas vibrantes y melancólicas, otras, de aire fantástico y alegre. Sin duda tales acordes reflejaban al exterior los ocultos pensamientos del músico, bien dándoles su definitiva forma, bien acompañándolos no más que como una caprichosa melodía del espíritu. Sabe Dios que no hubiera sufrido pasivamente esos exasperantes solos a no tener Holmes la costumbre de rematarlos con una rápida sucesión de mis piezas favoritas, ejecutadas en descargo de lo que antes de ellas había debido oír.

During the first week or so we had no callers, and I had begun to think that my companion was as friendless a man as I was myself. Presently, however, I found that he had many acquaintances, and those in the most different classes of society. There was one little sallow rat-faced, dark-eyed fellow who was introduced to me as Mr. Lestrade, and who came three or four times in a single week. One morning a young girl called, fashionably dressed, and stayed for half an hour or more. The same afternoon brought a grey-headed, seedy visitor, looking like a Jew pedlar, who appeared to me to be much excited, and who was closely followed by a slip-shod elderly woman. On another occasion an old white-haired gentleman had an interview with my companion; and on another a railway porter in his velveteen uniform. When any of these nondescript individuals put in an appearance, Sherlock Holmes used to beg for the use of the sitting-room, and I would retire to my bed-room. He always apologized to me for putting me to this inconvenience. "I have to use this room as a place of business," he said, "and these people are my clients." Again I had an opportunity of asking him a point blank question, and again my delicacy prevented me from forcing another man to confide in me. I imagined at the time that he had some strong reason for not alluding to it, but he soon dispelled the idea by coming round to the subject of his own accord.

Llevábamos juntos alrededor de una semana sin que nadie apareciese por nuestro habitáculo, cuando empecé a sospechar en mi compañero una orfandad de amistades pareja a la mía. Pero, según pude descubrir a continuación, no sólo era ello falso, sino que además los contactos de Holmes se distribuían entre las más dispersas cajas de la sociedad. Existía, por ejemplo, un hombrecillo de ratonil aspecto, pálido y ojimoreno, que me fue presentado como el señor Lestrade y que vino a casa en no menos de tres o cuatro ocasiones a lo largo de una semana. Otra mañana una joven elegantemente vestida fue nuestro huésped durante más de media hora. A la joven sucedió por la noche un tipo harapiento y de cabeza cana —la clásica estampa del buhonero judío—, que parecía hallarse sobre ascuas y que a su vez dejó paso a una raída y provecta señora. Un día estuvo mi compañero departiendo con cierto caballero anciano y de melena blanca como la nieve; otro, recibió a un mozo de cuerda que venía con su uniforme de pana. Cuando alguno de los miembros de esta abigarrada comunidad hacía acto de presencia, solía Holmes suplicarme el usufructo de la sala y yo me retiraba entonces a mi dormitorio. Jamás dejó de disculparse por el trastorno que de semejante modo me causaba. —Tengo que utilizar esta habitación como oficina —decía—, y la gente que entra en ella constituye mi clientela—. ¡Qué mejor momento para interrogarle a quemarropa! Sin embargo, me vi siempre sujeto por el recato de no querer forzar la confidencia ajena. Imagina que algo le impedía dejar al descubierto ese aspecto de su vida, cosa que pronto me desmintió él mismo yendo derecho al asunto sin el menor requerimiento por mi parte.

It was upon the 4th of March, as I have good reason to remember, that I rose somewhat earlier than usual, and found that Sherlock Holmes had not yet finished his breakfast. The landlady had become so accustomed to my late habits that my place had not been laid nor my coffee prepared. With the unreasonable petulance of mankind I rang the bell and gave a curt intimation that I was ready. Then I picked up a magazine from the table and attempted to while away the time with it, while my companion munched silently at his toast. One of the articles had a pencil mark at the heading, and I naturally began to run my eye through it.

Se cumplía como bien recuerdo el 4 de marzo, cuando, habiéndome levantado antes que de costumbre, encontré a Holmes despachando su aún inconcluso desayuno. Tan hecha estaba la patrona a mis hábitos poco madrugadores, que no hallé ni el plato aparejado ni el café dispuesto. Con la característica y nada razonable petulancia del común de los mortales, llamé entonces al timbre y anuncié muy cortante que esperaba mi ración. Acto seguido tomé un periódico de la mesa e intenté distraer con él el tiempo mientras mi compañero terminaba en silencio su tostada. El encabezamiento de uno de los artículos estaba subrayado en rojo, y a él, naturalmente, dirigí en primer lugar mi atención.

Its somewhat ambitious title was "The Book of Life," and it attempted to show how much an observant man might learn by an accurate and systematic examination of all that came in his way. It struck me as being a remarkable mixture of shrewdness and of absurdity. The reasoning was close and intense, but the deductions appeared to me to be far-fetched and exaggerated. The writer claimed by a momentary expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye, to fathom a man's inmost thoughts. Deceit, according to him, was an impossibility in the case of one trained to observation and analysis. His conclusions were as infallible as so many propositions of Euclid. So startling would his results appear to the uninitiated that until they learned the processes by which he had arrived at them they might well consider him as a necromancer.

Sobre la raya encarnada aparecían estas ampulosas palabras: EL LIBRO DE LA VIDA, y a ellas seguía una demostración de las innumerables cosas que a cualquiera le sería dado deducir no más que sometiendo a examen preciso y sistemático los acontecimientos de que el azar le hiciese testigo. El escrito se me antojó una extraña mezcolanza de agudeza y disparate. A sólidas y apretadas razones sucedían inferencias en exceso audaces o exageradas. Afirmaba el autor poder adentrarse, guiado de señales tan someras como un gesto, el estremecimiento de un músculo, o la mirada de unos ojos, en los más escondidos pensamientos de otro hombre. Según él, la simulación y el engaño resultaban impracticables delante de un individuo avezado al análisis y a la observación. Lo que éste dedujera sería tan cierto como las proposiciones de Euclides. Tan sorprendentes serían los resultados, que el no iniciado en las rutas por donde se llega de los principios a las conclusiones, habría por fuerza de creerse en presencia de un auténtico nigromante.

"From a drop of water," said the writer, "a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other. So all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it. Like all other arts, the Science of Deduction and Analysis is one which can only be acquired by long and patient study nor is life long enough to allow any mortal to attain the highest possible perfection in it. Before turning to those moral and mental aspects of the matter which present the greatest difficulties, let the enquirer begin by mastering more elementary problems. Let him, on meeting a fellow-mortal, learn at a glance to distinguish the history of the man, and the trade or profession to which he belongs. Puerile as such an exercise may seem, it sharpens the faculties of observation, and teaches one where to look and what to look for. By a man's finger nails, by his coat-sleeve, by his boot, by his trouser knees, by the callosities of his forefinger and thumb, by his expression, by his shirt cuffs—by each of these things a man's calling is plainly revealed. That all united should fail to enlighten the competent enquirer in any case is almost inconceivable."

—A partir de una gota de agua —decía el autor—, cabría al lógico establecer la posible existencia de un océano Atlántico o unas cataratas del Niágara, aunque ni de lo uno ni de lo otro hubiese tenido jamás la más mínima noticia. La vida toda es una gran cadena cuya naturaleza se manifiesta a la sola vista de un eslabón aislado. A semejanza de otros oficios, la Ciencia de la Deducción y el Análisis exige en su ejecutante un estudio prolongado y paciente, no habiendo vida humana tan larga que en el curso de ella quepa a nadie alcanzar la perfección máxima de que el arte deductivo es susceptible. Antes de poner sobre el tapete los aspectos morales y psicológicos de más bulto que esta materia suscita, descenderé a resolver algunos problemas elementales. Por ejemplo, cómo apenas divisada una persona cualquiera, resulta hacedero inferir su historia completa, así como su oficio o profesión. Parece un ejercicio pueril, y sin embargo afina la capacidad de observación, descubriendo los puntos más importantes y el modo como encontrarles respuesta. Las uñas de un individuo, las mangas de su chaqueta, sus botas, la rodillera de los pantalones, la callosidad de los dedos pulgar e índice, la expresión facial, los puños de su camisa, todos estos detalles, en fin, son prendas personales por donde claramente se revela la profesión del hombre observado. Que semejantes elementos, puestos en junto, no iluminen al inquisidor competente sobre el caso más difícil, resulta, sin más, inconcebible.

"What ineffable twaddle!" I cried, slapping the magazine down on the table, "I never read such rubbish in my life."

—¡Valiente sarta de sandeces! —grité, dejando el periódico sobre la mesa con un golpe seco—. Jamás había leído en mi vida tanto disparate.

"What is it?" asked Sherlock Holmes.

—¿De qué se trata? —preguntó Sherlock Holmes.

"Why, this article," I said, pointing at it with my egg spoon as I sat down to my breakfast. "I see that you have read it since you have marked it. I don't deny that it is smartly written. It irritates me though. It is evidently the theory of some arm-chair lounger who evolves all these neat little paradoxes in the seclusion of his own study. It is not practical. I should like to see him clapped down in a third class carriage on the Underground, and asked to give the trades of all his fellow-travellers. I would lay a thousand to one against him."

—De ese artículo —dije, apuntando hacia él con mi cucharilla mientras me sentaba para dar cuenta de mi desayuno—. Veo que lo ha leído, ya que está subrayado por usted. No niego habilidad al escritor. Pero me subleva lo que dice. Se trata a ojos vista de uno de esos divagadores de profesión a los que entusiasma elucubrar preciosas paradojas en la soledad de sus despachos. Pura teoría. ¡Quién lo viera encerrado en el metro, en un vagón de tercera clase, frente por frente de los pasajeros, y puesto a la tarea de ir adivinando las profesiones de cada uno! Apostaría uno a mil en contra suya.

"You would lose your money," Sherlock Holmes remarked calmly. "As for the article I wrote it myself."

—Perdería usted su dinero —repuso Holmes tranquilamente—. En cuanto al artículo, es mío.

"You!"

—¡Suyo!

"Yes, I have a turn both for observation and for deduction. The theories which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so chimerical are really extremely practical—so practical that I depend upon them for my bread and cheese."

—Sí; soy aficionado tanto a la observación como a la deducción. Esas teorías expuestas en el periódico y que a usted se le antojan tan quiméricas, vienen a ser en realidad extremadamente prácticas, hasta el punto que de ellas vivo.

"And how?" I asked involuntarily.

—¿Cómo? —pregunté involuntariamente.

"Well, I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the world. I'm a consulting detective, if you can understand what that is. Here in London we have lots of Government detectives and lots of private ones. When these fellows are at fault they come to me, and I manage to put them on the right scent. They lay all the evidence before me, and I am generally able, by the help of my knowledge of the history of crime, to set them straight. There is a strong family resemblance about misdeeds, and if you have all the details of a thousand at your finger ends, it is odd if you can't unravel the thousand and first. Lestrade is a well-known detective. He got himself into a fog recently over a forgery case, and that was what brought him here."

—Tengo un oficio muy particular, sospecho que único en el mundo. Soy detective asesor... Verá ahora lo que ello significa. En Londres abundan los detectives comisionados por el gobierno, y no son menos los privados. Cuando uno de ellos no sabe muy bien por dónde anda, acude a mí, y yo lo coloco entonces sobre la pista. Suelen presentarme toda la evidencia de que disponen, a partir de la cual, y con ayuda de mi conocimiento de la historia criminal, me las arreglo decentemente para enseñarles el camino. Existe un fuerte aire de familia entre los distintos hechos delictivos, y si se dominan a la menuda los mil primeros, no resulta difícil descifrar el que completa el número mil uno. Lestrade es un detective bien conocido. No hace mucho se enredó en un caso de falsificación, y hallándose un tanto desorientado, vino aquí a pedir consejo.

"And these other people?"

—¿Y los demás visitantes?

"They are mostly sent on by private inquiry agencies. They are all people who are in trouble about something, and want a little enlightening. I listen to their story, they listen to my comments, and then I pocket my fee."

—Proceden en la mayoría de agencias privadas de investigación. Son gente que está a oscuras sobre algún asunto y acude a buscar un poco de luz. Atiendo a su relato, doy mi opinión, y presento la minuta.

"But do you mean to say," I said, "that without leaving your room you can unravel some knot which other men can make nothing of, although they have seen every detail for themselves?"

—¿Pretende usted decirme —atajé— que sin salir de esta habitación se las compone para poner en claro lo que otros, en contacto directo con las cosas, e impuestos sobre todos sus detalles, sólo ven a medias?

"Quite so. I have a kind of intuition that way. Now and again a case turns up which is a little more complex. Then I have to bustle about and see things with my own eyes. You see I have a lot of special knowledge which I apply to the problem, and which facilitates matters wonderfully. Those rules of deduction laid down in that article which aroused your scorn, are invaluable to me in practical work. Observation with me is second nature. You appeared to be surprised when I told you, on our first meeting, that you had come from Afghanistan."

—Exactamente. Poseo, en ese sentido, una especie de intuición. De cuando en cuando surge un caso más complicado, y entonces es menester ponerse en movimiento y echar alguna que otra ojeada. Sabe usted que he atesorado una cantidad respetable de datos fuera de lo común; este conocimiento facilita extraordinariamente mi tarea. Las reglas deductivas por mí sentadas en el artículo que acaba de suscitar su desdén me prestan además un inestimable servicio. La capacidad de observación constituye en mi caso una segunda naturaleza. Pareció usted sorprendido cuando, nada más conocerlo, observé que había estado en Afganistán.

"You were told, no doubt."

—Alguien se lo dijo, sin duda.

"Nothing of the sort. I knew you came from Afghanistan. From long habit the train of thoughts ran so swiftly through my mind, that I arrived at the conclusion without being conscious of intermediate steps. There were such steps, however. The train of reasoning ran, 'Here is a gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor, then. He has just come from the tropics, for his face is dark, and that is not the natural tint of his skin, for his wrists are fair. He has undergone hardship and sickness, as his haggard face says clearly. His left arm has been injured. He holds it in a stiff and unnatural manner. Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have seen much hardship and got his arm wounded? Clearly in Afghanistan.' The whole train of thought did not occupy a second. I then remarked that you came from Afghanistan, and you were astonished."

—En absoluto. Me constaba esa procedencia suya de Afganistán. El hábito bien afirmado imprime a los pensamientos una tan rápida y fluida continuidad, que me vi abocado a la conclusión sin que llegaran a hacérseme siquiera manifiestos los pasos intermedios. Éstos, sin embargo, tuvieron su debido lugar. Helos aquí puestos en orden: «Hay delante de mí un individuo con aspecto de médico y militar a un tiempo. Luego se trata de un médico militar. Acaba de llegar del trópico, porque la tez de su cara es oscura y ése no es el color suyo natural, como se ve por la piel de sus muñecas. Según lo pregona su macilento rostro ha experimentado sufrimientos y enfermedades. Le han herido en el brazo izquierdo. Lo mantiene rígido y de manera forzada... ¿en qué lugar del trópico es posible que haya sufrido un médico militar semejantes contrariedades, recibiendo, además, una herida en el brazo? Evidentemente, en Afganistán». Esta concatenación de pensamientos no duró el espacio de un segundo. Observé entonces que venía de la región afgana, y usted se quedó con la boca abierta.

"It is simple enough as you explain it," I said, smiling. "You remind me of Edgar Allen Poe's Dupin. I had no idea that such individuals did exist outside of stories."

—Tal como me ha relatado el lance, parece cosa de nada —dije sonriendo—. Me recuerda usted al Dupin de Allan Poe. Nunca imaginé que tales individuos pudieran existir en realidad.

Sherlock Holmes rose and lit his pipe. "No doubt you think that you are complimenting me in comparing me to Dupin," he observed. "Now, in my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow. That trick of his of breaking in on his friends' thoughts with an apropos remark after a quarter of an hour's silence is really very showy and superficial. He had some analytical genius, no doubt; but he was by no means such a phenomenon as Poe appeared to imagine."

Sherlock Holmes se puso en pie y encendió la pipa.

—Sin duda cree usted halagarme estableciendo un paralelo con Dupin —apuntó—. Ahora bien, en mi opinión, Dupin era un tipo de poca monta. Ese expediente suyo de irrumpir en los pensamientos de un amigo con una frase oportuna, tras un cuarto de hora de silencio, tiene mucho de histriónico y superficial. No le niego, desde luego, talento analítico, pero dista infinitamente de ser el fenómeno que Poe parece haber supuesto.

"Have you read Gaboriau's works?" I asked. "Does Lecoq come up to your idea of a detective?"

—¿Ha leído usted las obras de Gaboriau? —pregunté—. ¿Responde Lecoq a su ideal detectivesco?

Sherlock Holmes sniffed sardonically. "Lecoq was a miserable bungler," he said, in an angry voice; "he had only one thing to recommend him, and that was his energy. That book made me positively ill. The question was how to identify an unknown prisoner. I could have done it in twenty-four hours. Lecoq took six months or so. It might be made a text-book for detectives to teach them what to avoid."

Sherlock Holmes arrugó sarcástico la nariz.

—Lecoq era un chapucero indecoroso —dijo con la voz alterada—, que no tenía sino una sola cualidad, a saber: la energía. Cierto libro suyo me pone sencillamente enfermo... En él se trata de identificar a un prisionero desconocido, sencillísima tarea que yo hubiera ventilado en veinticuatro horas y para la cual Lecoq precisa, poco más o menos, seis meses. Ese libro merecería ser repartido entre los profesionales del ramo como manual y ejemplo de lo que no hay que hacer.

I felt rather indignant at having two characters whom I had admired treated in this cavalier style. I walked over to the window, and stood looking out into the busy street. "This fellow may be very clever," I said to myself, "but he is certainly very conceited."

Hirió algo mi amor propio al ver tratados tan displicentemente a dos personas que admiraba. Me aproximé a la ventana, y tuve durante un rato la mirada perdida en la calle llena de gente. «No sé si será este tipo muy listo», pensé para mis adentros, «pero no cabe la menor duda de que es un engreído.»

"There are no crimes and no criminals in these days," he said, querulously. "What is the use of having brains in our profession. I know well that I have it in me to make my name famous. No man lives or has ever lived who has brought the same amount of study and of natural talent to the detection of crime which I have done. And what is the result? There is no crime to detect, or, at most, some bungling villany with a motive so transparent that even a Scotland Yard official can see through it."

—No quedan ya crímenes ni criminales —prosiguió, en tono quejumbroso—. ¿De qué sirve en nuestra profesión tener la cabeza bien puesta sobre los hombros? Sé de cierto que no me faltan condiciones para hacer mi nombre famoso. Ningún individuo, ahora o antes de mí, puso jamás tanto estudio y talento natural al servicio de la causa detectivesca... ¿Y para qué? ¡No aparece el gran caso criminal! A lo sumo me cruzo con alguna que otra chapucera villanía, tan transparente, que su móvil no puede hurtarse siquiera a los ojos de un oficial de Scotland Yard.

I was still annoyed at his bumptious style of conversation. I thought it best to change the topic.

Persistía en mí el enfado ante la presuntuosa verbosidad de mi compañero, de manera que juzgué conveniente cambiar de tercio.

"I wonder what that fellow is looking for?" I asked, pointing to a stalwart, plainly-dressed individual who was walking slowly down the other side of the street, looking anxiously at the numbers. He had a large blue envelope in his hand, and was evidently the bearer of a message.

—¿Qué tripa se le habrá roto al tipo aquél? —pregunté señalando a cierto individuo fornido y no muy bien trajeado que a paso lento recorría la acera opuesta, sin dejar al tiempo de lanzar unas presurosas ojeadas a los números de cada puerta. Portaba en la mano un gran sobre azul, y su traza era a la vista la de un mensajero.

"You mean the retired sergeant of Marines," said Sherlock Holmes.

—¿Se refiere usted seguramente al sargento retirado de la Marina? —dijo Sherlock Holmes.

"Brag and bounce!" thought I to myself. "He knows that I cannot verify his guess."

«¡Fanfarrón!», pensé para mí. «Sabe que no puedo verificar su conjetura.»

The thought had hardly passed through my mind when the man whom we were watching caught sight of the number on our door, and ran rapidly across the roadway. We heard a loud knock, a deep voice below, and heavy steps ascending the stair.

Apenas si este pensamiento había cruzado mi mente, cuando el hombre que espiábamos percibió el número de nuestra puerta y se apresuró a atravesar la calle. Oímos un golpe seco de aldaba, una profunda voz que venía de abajo y el ruido pesado de unos pasos a lo largo de la escalera.

"For Mr. Sherlock Holmes," he said, stepping into the room and handing my friend the letter.

Here was an opportunity of taking the conceit out of him. He little thought of this when he made that random shot. "May I ask, my lad," I said, in the blandest voice, "what your trade may be?"

—¡Para el señor Sherlock Holmes! —exclamó el extraño, y, entrando en la habitación, entregó la carta a mi amigo. ¡Era el momento de bajarle a éste los humos! ¡Quién le hubiera dicho, al soltar aquella andanada en el vacío, que iba a verse de pronto en el brete de hacerla buena!

Pregunté entonces con mi más acariciadora voz:

—¿Buen hombre, tendría usted la bondad de decirme cuál es su profesión?

"Commissionaire, sir," he said, gruffly. "Uniform away for repairs."

—Ordenanza, señor —dijo con un gruñido—. Me están arreglando el uniforme.

"And you were?" I asked, with a slightly malicious glance at my companion.

—¿Qué era usted antes? —inquirí mientras miraba maliciosamente a Sherlock Holmes con el rabillo del ojo.

"A sergeant, sir, Royal Marine Light Infantry, sir. No answer? Right, sir."

—Sargento, señor, sargento de infantería ligera de la Marina Real. ¿No hay contestación? Perfectamente, señor.

He clicked his heels together, raised his hand in a salute, and was gone.

Y juntando los talones, saludó militarmente y desapareció de nuestra vista.

Chapter III.

The Lauriston garden mistery

"The Lauriston garden mystery": the table-of-contents lists this chapter as "...gardens mistery"—plural, and probably more correct.

Capítulo tres

El misterio de Lauriston Gardens

I CONFESS that I was considerably startled by this fresh proof of the practical nature of my companion's theories. My respect for his powers of analysis increased wondrously. There still remained some lurking suspicion in my mind, however, that the whole thing was a pre-arranged episode, intended to dazzle me, though what earthly object he could have in taking me in was past my comprehension. When I looked at him he had finished reading the note, and his eyes had assumed the vacant, lack-lustre expression which showed mental abstraction.

No ocultaré mi sorpresa ante la eficacia que otra vez evidenciaban las teorías de Holmes. Sentí que mi respeto hacia tamaña facultad adivinatoria aumentaba portentosamente. Aun así, no podía acallar completamente la sospecha de que fuera todo un montaje enderezado a deslumbrarme en vista de algún motivo sencillamente incomprensible. Cuando dirigí hacia él la mirada, había concluido ya de leer la nota y en sus ojos flotaba la expresión vacía y sin brillo por donde se manifiestan al exterior los estados de abstracción meditativa.

"How in the world did you deduce that?" I asked.

—¿Cómo diantres ha llevado usted a cabo su deducción? —pregunté.

"Deduce what?" said he, petulantly.

—¿Qué deducción? —repuso petulantemente.

"Why, that he was a retired sergeant of Marines."

—Caramba, la de que era un sargento retirado de la Marina.

"I have no time for trifles," he answered, brusquely; then with a smile, "Excuse my rudeness. You broke the thread of my thoughts; but perhaps it is as well. So you actually were not able to see that that man was a sergeant of Marines?"

—No estoy para bagatelas —contestó de manera cortante; y añadió, con una sonrisa—: Perdone mi brusquedad, pero ha cortado usted el hilo de mis pensamientos. Es lo mismo... Así, pues, ¿no le había saltado a la vista la condición del mensajero?

"No, indeed."

—Puede estar seguro.

"It was easier to know it than to explain why I knew it. If you were asked to prove that two and two made four, you might find some difficulty, and yet you are quite sure of the fact. Even across the street I could see a great blue anchor tattooed on the back of the fellow's hand. That smacked of the sea. He had a military carriage, however, and regulation side whiskers. There we have the marine. He was a man with some amount of self-importance and a certain air of command. You must have observed the way in which he held his head and swung his cane. A steady, respectable, middle-aged man, too, on the face of him—all facts which led me to believe that he had been a sergeant."